Chapter 13 Dynamics of Multiple Pathogens

13.1 Overview and Learning Objectives

In this chapter, we will discuss scenarios where more than one infectious disease is considered simultaneously.

The learning objectives for this chapter are:

- Know important multi-ID systems

- Understand how IDs can interact

13.2 Introduction

So far, we focused on a single ID at a time. The main reason for this is simplicity. A single ID is already difficult to study and leads to complex dynamics. It makes sense to first study and understand individual IDs before including further IDs. That said, there are always many pathogens present at the same time, and infection with more than one ID is very common (Petney and Andrews 1998). This is true in the developed world with a fairly low ID burden, and even more so in developing countries. It is thus often useful to consider systems with more than one ID.

13.3 Interactions of ID

Sometimes, different IDs do not interact, i.e., being infected with one does not impact the susceptibility or course of infection for another ID. It is likely that some amount of interaction occurs for almost all IDs, mediated by the immune response or through other mechanisms such as a change in host behavior or host death (Rohani et al. 2003). However, unless the IDs are relatively common and the interaction effect is strong, it is often hard to determine if and how IDs affect each other. As such, we know how some IDs interact (e.g., TB and HIV) but for most ID, we have very little knowledge. The next few sections briefly discuss some IDs for which we have some understanding regarding interactions. This is not an exhaustive discussion. Instead, we focus on some of the best-known interactions.

13.3.1 HIV-TB Interactions

HIV is the pathogen that is best studied with regard to interaction with other pathogens (Karp and Auwaerter 2007b, 2007a; Griffiths et al. 2011). Arguably of most public health interest and concern is the interaction with TB. Having an (untreated) HIV infection makes it much more likely for an individual latently infected with TB to develop TB disease. Further, once TB disease develops, an individual who is also infected with HIV has worse symptoms and a much higher chance of dying (Pawlowski et al. 2012). An important current question that is still not fully answered is if the suppression of HIV by antiretroviral therapy treatment removes all detrimental effects of HIV on TB progression, or if the presence of HIV, albeit at minuscule levels, still has a negative impact on TB disease progression.

13.3.2 HIV-Hepatitis Interactions

Persons infected with HIV are also often at risk of having HBV or HCV infections. The primary reason for this is that risk factors for these pathogens are very similar (e.g., drug use) (Sulkowski 2008). Co-infection leads to faster rate of liver failure (Chen, Feeney, and Chung 2014). If HBV or HCV leads to more rapid progression to AIDS and HIV-mediated death is unclear (Kim and Chung 2009). It seems that with antiretroviral therapy and the new drugs against viral hepatitis, the impact of this co-infection on health can be minimized.

13.3.3 Influenza-Strep Interactions

The interaction of influenza with some bacteria and most notably Streptococcus pneumoniae has been somewhat well studied (McCullers 2006). Some careful animal experiments, as well as modeling studies, have shown how influenza interacts with bacteria co-infections (A. M. Smith and McCullers 2014; Shrestha et al. 2013). In general, an influenza infection seems to make it more likely - during a short time window - to have a subsequent bacterial infection, and the outcome of the bacterial infection is often worse. It is still not well understood if there is also an effect of a respiratory bacterial infection on a potential secondary influenza infection (Davis et al. 2012).

13.4 More Than Two Infectious Diseases

While not much is known about interactions between any two ID (apart from the examples just described and a few others), even less is known for 2+ ID. It is fair to say that given our current level of knowledge about the biology and epidemiology of various ID, understanding interactions and dynamics of multiple ID is beyond our current scope, and will likely remain so for a while.

13.5 Multiple ID and Control

If multiple IDs are present, it makes sense to try and implement control strategies against as many of them as possible. This is true for diseases which interact or are independent. Unfortunately, given the way health systems are structured and funded, it is still often the case that interventions target a single ID at a time. E.g., a campaign against malaria focuses solely on malaria treatment, even though many of the patients probably also have TB or some helminth infections and should be tested and treated for those diseases at the same time. The one important exception is HIV. Often HIV testing and treatment is included even if a study or health campaign focuses on a different disease. Having a more wide-spread multi-ID approach to control would very likely be highly effective since, for many ID, individuals who are likely to get infected with one are also likely to get infected with other ID. This is because many IDs have the same risk factors for transmission from poor nutrition or unsanitary conditions to particular behaviors that increase the risk for multiple IDs. One could, therefore, efficiently find and effectively treat many different IDs. Public health is slowly moving this direction.

Some ways in which multiple IDs are controlled are almost accidental. It is well known that better education, better nutrition, better standard of living, improved sanitation and housing all reduce morbidity and mortality to a large number of diseases. As developing countries become richer and people escape extreme poverty, the incidence of many IDs fall. This is the trajectory many developed countries were on, e.g., TB incidence in Europe was falling rapidly even before the introduction of anti-TB drugs. As more countries become developed, the ID burden will decline (and likely with it, “wealth diseases” like obesity will rise).

13.5.0.1 Modeling multiple ID

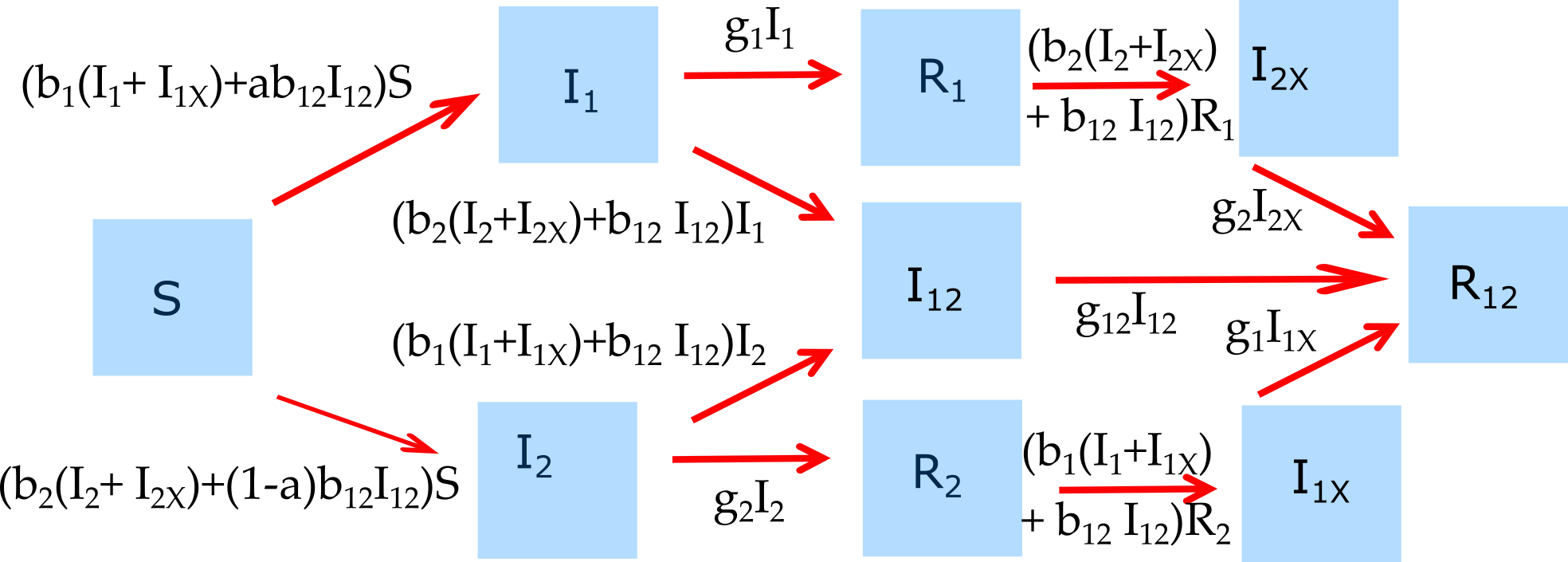

The approach to modeling multiple ID is similar to that of host heterogeneity: We need to split/stratify the population according to infection status of each ID. The complicated part is modeling any potential interactions between IDs correctly. As mentioned previously, more compartments the more complex the model becomes. Making it harder to code, analyze, and we need estimates for each parameter, which are often hard to get. Because of that, considering/modeling more than 2 ID is still almost never done - but many critical 2-ID modeling studies exist. Figure 13.1 shows the diagram for a 2 ID model.

FIGURE 13.1: Example of a model that considers 2 ID.

The differential equations corresponding to this diagram are given by:

\[\dot S = - (b_{1} (I_1+I_{1X}) + b_{2} (I_2+I_{2X}) + b_{12}I_{12}) S \] \[\dot I_1 = (b_{1} (I_1+I_{1X}) + ab_{12} I_{12})S - (g_1 + b_{2} (I_2+I_{2X}) + b_{12} I_{12}) I_1\] \[\dot I_2 = (b_{2} (I_2+I_{2X}) + (1-a) b_{12} I_{12})S - (g_2 + b_{1}(I_1 + I_{1X}) + b_{12} I_{12}) I_2\] \[\dot I_{12} = (b_{2} (I_2+I_{2X}) + b_{12} I_{12}) I_1 + (b_{1}(I_1 + I_{1X}) + b_{12} I_{12}) I_2 - g_{12} I_{12}\] \[\dot R_1 = g_1 I_1 - (b_2 (I_2 + I_{2X}) + b_{12} I_{12}) R_1\] \[\dot R_2 = g_2 I_2 - (b_1 (I_1 + I_{1X}) + b_{12} I_{12}) R_2\] \[\dot I_{1X} = (b_1 (I_1 + I_{1X}) + b_{12} I_{12}) R_2 - g_{1} I_{1X}\] \[\dot I_{2X} = (b_2 (I_2 + I_{2X}) + b_{12} I_{12}) R_1 - g_{2} I_{2X}\] \[\dot R_{12} = g_{1} I_{1X} + g_{2} I_{2X} + g_{12} I_{12} \]

13.6 Summary and Cartoon

This chapter discussed multi-pathogen systems.

I don’t have a topical cartoon, so instead just a random one. Let me know if you find a suitable one!

13.7 Exercises

- The Multi-pathogen dynamics app in the DSAIDE package provides hands-on computer exercises for this chapter.

- Read the article “The nature and consequences of coinfection in humans” by Griffiths et al. (Griffiths et al. 2011). They report that for several of the “top 10” ID no co-infection studies could be found among 2009 publications. See if you can find any coinfection studies on one of those IDs that were published since. Describe and summarize the studies you found.

13.8 Further Resources

- The references mentioned in this chapter provide further information on specific topics.

- An interesting modeling study looking at potential interactions of HIV and Malaria is (Abu-Raddad, Patnaik, and Kublin 2006).

- A review of possible interactions between TB and parasitic infections can be found in (X.-X. Li and Zhou 2013).

- A very nice analysis of the impact of measles and measles vaccination on other childhood infectious diseases is given in (Mina et al. 2015).