Chapter 7 Modes of Direct Transmission

7.1 Overview and Learning Objectives

In this chapter, we will discuss different types of direct transmission and explore how these different modes of transmission impact ID dynamics.

The learning objectives for this chapter are:

- Assess how different modes of direct transmission affect ID dynamics.

- Contrast the difference between density- and frequency-dependent transmission.

- Predict how population size impacts ID dynamics for different types of transmission.

7.2 Introduction

The direct transmission of a pathogen means it goes straight from an infected host to a new uninfected host. Sounds simple enough, but as we’ll discuss here straight from host to host is in fact not that straightforward, and many pathogens have both direct and indirect transmission components. We’ll discuss the most important direct transmission types and what hosts fall under that umbrella.

7.3 Contact transmission

The most straightforward way of transmission is through direct contact between infected and uninfected hosts. A prime class of pathogens that follow this route are sexually transmitted infections (STI). For STIs, the pathogen goes directly from one host to the other. Another pathogen for which direct contact is an important (but not the only) route of transmission is Ebola.

A particular group of contact transmission is vertical transmission between mother and child. This type of transmission is important for diseases such as HIV or Ebola. To describe vertical transmission, one needs to account for at least two different types of hosts, namely mothers and children. We will consider different types of hosts and how they can be represented in models in chapter 10.

7.4 Airborne transmission

Some pathogens are essentially direct with only a very short time spent outside the host. Many respiratory infections fall in this category. Those pathogens are often expelled as small air drops by the host (through breathing, sneezing or coughing) and then are quickly inhaled by an uninfected host, thus potentially causing a new infection. Similarly, a pathogen might for a brief time be deposited on a surface (e.g., a bathroom faucet). Such a potentially infected surface is often called a fomite. If the pathogen is picked up fairly quickly by an uninfected host and thus completes the transmission process, it is sometimes also reasonable to consider this an essentially direct transmission process.

The decision to consider airborne or surface mediated transmission direct or indirect transmission is very much dependent on the perspective and focus of the question one wants to address. For some questions and situations, assuming this route of transmission to be essentially direct is reasonable. For instance, for a large-scale simulation of a flu pandemic, it is usually a reasonable assumption to consider transmission directly between infected and uninfected hosts, without explicitly considering an environmental stage. In contrast, if one wants to study the transmission process in detail, it might be necessary to consider the short time the pathogen explicitly spends in the environment and thus using the perspective discussed in the Environmental Transmission chapter.

7.5 Ways in which direct transmission scales

For direct transmission, there are important ways in which transmission can scale with population size or population density. One often distinguishes between density-dependent and frequency-dependent transmission. Unfortunately, the terminology is not very consistent. Other terms are used and sometimes misused. See, e.g. Begon et al. (2002) for a discussion of this.

The main differences between these two types of transmission have to do with the scaling of transmission intensity (often measured by the force of infection) as population size changes. This is a feature of the number of contacts that a susceptible has with an infected person. For some types of ID, e.g., STI, the number of contacts (i.e., sexual encounters) is likely not too dependent on the population density or size. For instance, the average person living in a town of 100,000 people likely has pretty much the same number of sexual contacts compared to the person living in a town of 1 million. One could argue that more opportunities might lead to more sexual contacts, but it’s unlikely to change by much. This type of invariance of transmission is labeled (using the terminology of Begon et al. (2002)) frequency-dependent.

In contrast, for some ID, more individuals (given a constant area) leads to more contacts and more transmission. This might apply to ID such as influenza or norovirus. A scenario where an increase in population size/density leads to a (linear) increase in transmission is usually referred to as density-dependent transmission. However, even for ID that do show some signs of density dependence, the number of social contacts often dominates. For instance, a person in a city that is 10 times the size of a smaller city likely won’t have 10 times as many contacts.

7.5.1 Modeling types of direct transmission

Assuming the simple SIR model, we have the set of equations \[ \begin{aligned} \dot S &= - \lambda S \\ \dot I &= \lambda S - \gamma I \\ \dot R &= \gamma I. \end{aligned} \] The force of infection, \(\lambda\) - is equal to bI. The force of infection can be rewritten in a different form, namely \(\lambda= cpv\), where c is the rate of contacts between hosts, p is the probability that a contact is with an infected host and v is the probability that transmission occurs during contact. As an example, for HIV, c would measure the frequency of sexual encounters, p would quantify the fraction of those encounters that happen with an HIV+ individual, and p quantifies the probability that having sex with an HIV+ individual leads to infection.

Now, depending on the specific assumptions we make for the different parameters, we can end up with different types of transmission. We often assume that the probability that a contact is with an infected host is equal to the prevalence of the ID in the population, i.e., p = I/N. This is the so-called well-mixed population assumption and holds for both frequency- and density-dependent SIR type models. If we wanted to relax this assumption, we would need to switch to for instance network-based models or build more complicated compartmental models.

For density-dependent transmission, we assume that the rate of contacts is proportional to the density of hosts, i.e., c = kN/A, where N is the population size and A the area, and k is some constant of proportionality. As stated above, this might be a good approximation for some ID and scenarios, e.g., influenza.

For frequency-dependent transmission, we assume that the rate of contacts is fixed and independent of the density of hosts, i.e., c = f. This might be a good approximation, e.g., sexually transmitted diseases, where the number/density of individuals in the vicinity of an individual does not (or only in a small way) influence the rate at which a person has sexual contacts. We therefore end up with \(\lambda_d= kv I/A\) and \(\lambda_f= fv I/N\) for density- and frequency- dependent transmission, respectively. The terms kv and fv are often combined into a new parameter, bd and bf. If population size and area are fixed, the transmission types lead to the same results, as long as parameter values are chosen accordingly. If population size changes (not uncommon) or area changes (less common), one needs to be more careful with the choice of transmission term.

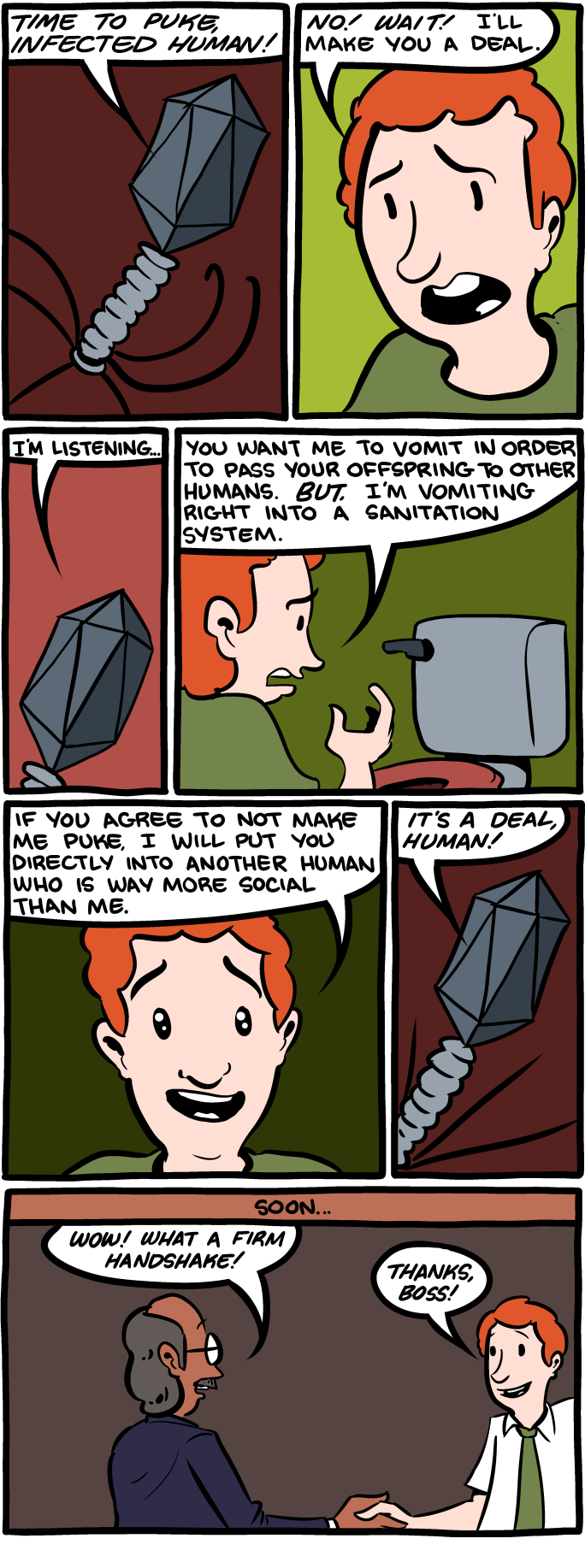

7.6 Summary and Cartoon

This chapter described different assumptions for direct transmission models and how they lead to different results with regard to disease dynamics and potential control strategies.

Some pathogens have direct and more indirect modes of transmission. Source: smbc-comics.com

7.7 Exercises

- The Direct transmission app in the DSAIDE package provides hands-on computer exercises for this chapter.

- Read the paper “How should pathogen transmission be modelled?” by McCallum et al. (H. McCallum, Barlow, and Hone 2001). The authors discuss different models for (direct) transmission. They claim that it matters in a practical setting to get the transmission term right. Pick some ID and explain how different assumptions about transmission might lead to different conclusions concerning possible control strategies.

7.8 Further Resources

- The paper (Begon et al. 2002) provides some additional information and discussion on the topic of direct transmission types and how they should be modeled.

- In (Ferrari et al. 2011), the authors discuss transmission scaling and connect it to network models. (This book briefly discusses networks in the Networks chapter).