Chapter 9 Vector-borne Transmission

9.1 Overview and Learning Objectives

In this chapter, we will discuss an important form of indirect transmission, one that has a vector stage.

The learning objectives for this chapter are:

- Know about important IDs that are vector-borne

- Understand the implications of vector-borne transmission on ID dynamics

- Understand how vector-borne transmission influences potential ID control strategies.

9.2 Introduction

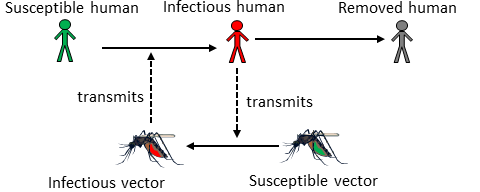

Vector-borne IDs are those that go through - at least - two different hosts to complete a full replication and transmission cycle. Hosts of one type infect hosts of the other, and there is no direct transmission between hosts of the same type, except some cases of vertical transmission.

Schematic of a vector-borne ID

Not surprisingly, the IDs which receive the most study are those where one of the hosts are humans. The other host (i.e., the vector) can be any other animal, such as dogs, rodents, snails, insects, etc. At times, growth and replication of the pathogen occur mainly in one host, with the other just serving as a vessel to get between hosts. Most often, the pathogen completes significant parts of its growth and replication cycle in both (or all, if there are more than 2) hosts.

9.3 Vector-borne Transmission and ID Patterns

Understanding what mechanisms lead to potentially observed patterns in incidence and prevalence for vector-borne diseases is difficult, due to the presence of more than one host. In a previous chapter, we discussed cycles that could be caused by the intrinsic transmission dynamics or influenced by external drivers (e.g., seasonal changes in weather). This general concept still holds, but there are now two species (e.g., humans and mosquitos), both have distinct and intrinsic dynamics and responding differently to external factors. This obviously adds a lot of complexity to the model. Nevertheless, patterns in ID dynamics are often observed for vector-borne diseases and are at least partially understood. For instance, the reproductive cycle of mosquitos strongly depends on the weather, and specifically the availability or lack of water. As such, in regions that have strong differences in rainfall between seasons, one often observes annual cycles based on annual weather patterns.

9.4 Vector-borne Transmission and Interventions

With vector-borne ID, there is a unique opportunity for interventions that do not exist for directly transmitted diseases. Namely, we can try to control the ID at the vector stage. That often means trying to kill as many vectors as possible. DDT in the past and more recently pesticide-coated bed nets have been proven to work very effectively. Unfortunately, these interventions need to be sustained. Otherwise, mosquito numbers (or other vectors with a short lifespan) quickly bounce back. Also, while we mostly think of mosquitos and other insects as a nuisance or worse, they do perform important roles in the ecosystem, and it is unclear what the consequences would be of potentially killing all Anopheles mosquitos (they transmit a lot of important IDs). Some recent approaches try to make mosquitos resistant to ID. If one could introduce those and have them out-compete the mosquitos that are susceptible to the ID, one might - in theory - get rid of relevant IDs without affecting the ecosystem in unpredictable ways.

A major problem with all control strategies targeting vectors is that not only do pathogens evolve quickly, but most vectors have fairly short life spans and large population numbers, which means rapid evolution. That could result in wide spread resistance making any control measures ineffective within a short time. Indeed, that was observed for DDT, where mosquitos resistant to the chemical started to appear before its widespread use was discontinued.

9.4.0.1 Modeling Vector-borne Transmission

The easiest way to model a vector-borne disease is to simply ignore the vector and assume that the transmission term of the equation (e.g., a term like bSI) represents – in a very simplified form – all the complicated processes involved in transmission, including the vector stage. That makes the model simple, but of course, doesn’t capture the vector-borne aspects of the dynamics. If we are interested in the dynamics of the disease in all hosts, we do need to include the vector components in a model. To add vectors in a model, one could, for instance, build 2 SIR-type models, with one set of equations for the (human) host and one for the vector, and then couple the compartments by including transmission from humans to vectors and vectors to humans. Equations for such a model might look as follows: \[ \begin{aligned} \dot S_h &= - b_1 S_h I_v \\ \dot I_h &= b_1S_h I_v - g_h I_h \\ \dot R_h &= g_h I_h \\ \dot S_v &= - b_2 S_v I_h \\ \dot I_v &= b_2 S_v I_h - g_v I_v \\ \dot R_v &= g_v I_v \end{aligned} \] Here, the index h indicates humans and v indicates vectors. The important vector-borne aspect of such a model is that transmission only occurs from hosts to vector and vector to host, not between hosts or vectors. In general, the above model needs to be modified to more accurately describe vector-borne ID dynamics. For instance, many vectors have a fairly short natural lifespan, and as such their births and deaths need to be included in the model, even if the timescale in which we investigate the model is short enough to allow us to ignore births and deaths for (human) hosts. It is common to include more details in the human part of the model (e.g., asymptomatic stage and others as discussed previously) and less detail for the vector part. The specific details that should be included are driven by the question one wants to study.

9.4.0.2 Vectorial Capacity

Vector-borne transmission models have been instrumental in conceptualizing public health interventions. Seminal works of Sir Ronald Ross and George MacDonald and other talented researchers established a legacy of vector-borne disease transmission models, still found to this day called Ross-MacDonald family models. These models and their derivatives demonstrated what would come to be known as vectorial capacity, a measure that corresponds to the entomological components of the basic reproductive number, \(R_0\). In the context of the work on malaria, vectorial capacity estimations consist of parameters corresponding to the ratio of mosquitoes to humans, the human biting rate, the daily probability of mosquito survival, and the estimated duration of the latency period or parasite development rate in the mosquito; altogether, these parameters may yield an estimate for the number of infectious bites to eventually arise from a single day of mosquitoes feeding on a single infectious host (D. L. Smith et al. 2012).

Through the development of a vector-borne transmission model with such explicit parameterization to aspects of mosquito biology, Ross was able to identify a parameter to which the model was extremely sensitive (i.e., changes in this parameter caused great changes in the dynamics of the model). This parameter was the ratio of mosquitoes to humans. What resulted was a still-relevant and oft-employed public health intervention: vector control.

9.5 Summary and Cartoon

Vector-borne transmission adds complexity to an ID, but also allows for a wider range of control measures (such as vector killing).

There are multiple reasons mosquitos are not popular. Source: xkcd

9.6 Exercises

- The Vector transmission app in the DSAIDE package provides hands-on computer exercises for this chapter.

- Nominate an ID as a contender for having the ‘craziest or most complicated’ mode(s) of transmission. Explain the transmission dynamics for your nomination and justify why it deserves the title of craziest or most complicated. This doesn’t have to be a vector-borne disease, though some of the “crazy” ones tend to use multiple hosts.

9.7 Further Resources

- The following papers provide some additional discussion of vector-borne diseases and how to model them (D. L. Smith et al. 2014; Kilpatrick and Randolph 2012; Luz, Struchiner, and Galvani 2010).