Chapter 11 Infectious Disease Control

11.1 Overview and Learning Objectives

This chapter provides a closer look at different types of control against infectious diseases and their potential outcomes.

The learning objectives for this chapter are:

- Know the major types of ID control strategies

- Evaluate the use of different ID control strategies

- Understand how different pathogens require different types of control

11.2 Introduction

Generally, the reason why we study IDs and their dynamics is to eventually do something. We want to implement control and intervention strategies to minimize disease burden. That could be trying to contain an ongoing outbreak, reduce the incidence of an endemic disease, or try to eradicate a disease. Depending on modes of transmission, infectiousness profiles and other ID characteristics, the types of interventions that are available and potentially useful will vary. Therefore, the better we understand an ID, the better we can likely implement control.

11.3 Goals of ID Control

When trying to control an ID, we often have more than one goal in mind. The following are a list of (overlapping) public health goals that we often try to achieve with ID control:

- Reduce morbidity

- Reduce mortality

- Reduce transmission

- Reduce incidence/prevalence

- Reduce economic impact

- Minimize ethical or moral dilemmas

- Protect the individual

- Protect the population

Most of these goals are overlapping. E.g., reducing transmission likely reduces overall morbidity and mortality. Sometimes, goals can be conflicting. For instance, if we have limited resources, should we target those that are most likely to transmit but not suffer much from the disease (e.g., children) or target those that are most likely to experience morbidity/mortality but are not that necessary for transmission (e.g., elderly)? Similarly, at what level is it acceptable to force people to (not) do something (e.g., forced vaccination or quarantine) that might not help - and maybe even slightly hurt - the individual, but will be beneficial to society? Answers to those questions are usually beyond the scope of just ID Epidemiology. What we can contribute to the wider discussion is an assessment of the impact of various control strategies. That information can then be combined with other considerations to make decisions.

11.4 Types of Infectious Disease Control

The types of control and intervention strategies that exist for a given ID vary. Some depend on the route of transmission. Others depend on our skills and ability, e.g., our ability to produce a vaccine. The following sections describe the major types of ID control.

11.4.1 Vaccination

Vaccines are arguably the most cost effective public health intervention we have. An ideal vaccine is one that has only to be given once to induce lifelong protection against the ID. It should also be safe, with little to no side effects. Other characteristics of a good vaccine are ease of administration, low price and easy to transport and store.

The only IDs we have been able to eradicate so far (smallpox and rinderpest) are those against which we have good vaccines. Unfortunately, a good vaccine alone does not mean eradication is likely. Measles is a good example. We have a good vaccine, but the pathogen is so highly transmissible that coverage would need to be at levels beyond those currently achievable.

11.4.2 Pharmaceutical Interventions (Drugs)

Drugs are another very effective means of combating ID. While vaccines try to prevent infection (i.e., primary prevention), drugs act to reduce severity in already infected individuals (i.e., tertiary prevention).

It is important to understand that many drugs directly target the signs and/or symptoms of a disease (e.g., fever, cough, congestion) by, sometimes, acting antagonistically with the immune system response. The immune system is very complex and highly regulated and these characteristics allow us to ward off myriad threats including common pathogens, but sometimes its reaction to stimulus (e.g., infection) can be harmful. The harmful effects can vary in intensity from negligible cell/tissue damage to something as severe as systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS, a.k.a sepsis).

Other types of drugs, antimicrobials, act directly on the infectious agents. Generally, they are either microbiostatic (i.e., prevent microbe growth, e.g., erythromycin) or microbicidal (i.e., kill microbes, e.g., penicillin). While the mechanisms of action vary among antimicrobials, most all work in helping natural immunity develop.

The use of drugs to reduce symptoms and/or combat infectious agents might or might not impact transmission dynamics. A good example where treatment reduces infectiousness and transmission is treatment for HIV infected individuals. Highly-active antiretroviral therapy (HAART, sometimes simple referred to as ART) act to prevent HIV from making copies of itself, reduces the viral load (i.e., the concentration of virus in the body) to undetectable levels, and, consequently, greatly reduces the probability of transmission.

While not commonly used, drugs can also be given to susceptibles as prophylaxis to reduce the risk of infection. As such, one can think of drugs as short-term vaccines though the mechanism of protection is very different. Again, HIV is a case in point, where pre-exposure prophylaxis with ART has recently been shown to be somewhat effective in reducing the risk of infection.

For some IDs, such as, helminth infections, mass drug treatment is also being used to try and reduce ID prevalence enough to interrupt transmission and potentially eliminate the ID.

Another type of intervention, not strictly pharmaceutical by definition but worth mentioning, is serum therapy. Serum therapy basically consists of taking the blood sera from someone who was previously infected and/or is now immune and transferring it to someone who is currently susceptible or infected. The blood sera may contain antibodies that can target specific infectious agents. This is often referred to as passive immunity as opposed to the aforementioned active immunity mechanisms (e.g., natural immunity following infection or artificial immunity via vaccination). A well-known form of passive immunity is the transfer of protective antibodies from mother to baby, either in utero or through breast feeding. Whether from mother to baby or serum therapy, the passive immunity is only temporary (i.e., it is not long lasting as compared to the forms of active immunity).

For our modeling perspective, the most important distinction among these interventions is the duration of the effects. While some interventions (e.g., vaccination) may effectively transition a portion of the susceptible population directly to a removed compartment permanently, other mentioned interventions would be temporary and have more complex effects. For example, an intervention of pre-exposure prophylaxis may place susceptibles into a removed compartment for an amount of time dependent on the pharmacokinetics of the drug (e.g., how long it remains in your system). As another example, if we were to track a childhood infections, it may be important to consider passive immunity from mother to baby. For the first ~6 months after birth, the infants may be less susceptible to infectious disease as compared with older children. This duration of ~6 months corresponds to the length of time maternal antibodies are active and present, as they will decay over time. So, it would be necessary to either have a separate compartment for newborns or to parameterize transmissibility or susceptibility as a function of age (e.g., with partial differential equations).

11.4.3 Non-pharmaceutical Interventions

These are the oldest types of interventions and are often quite effective. In the Middle Ages during times of widespread plague (bacterial infections of Yersinia pestis), it became common for coastal cities to force newly-arriving ships to not disembark for 40 days. The reasoning behind this was to wait and see if anyone on the ship was infected with plague before allowing them to enter the city. This is the origin of a now common word, quarantine (from the Italian root of forty). Our current definition of quarantine does not specifically refer to a forty day period, but instead focuses on the separation of potentially exposed persons from others for an amount of time dependent on the characteristics of a particular ID (recall latency and incubation periods from the Characteristics of ID chapter). A related, yet distinct, concept is isolation which refers to the separation of infected persons from others for an amount of time commensurate with a specific ID characteristics. It is important to remark on the difference between these two interventions. While isolation separates those who are actively infected (likely infectious, and more than likely symptomatic), quarantine separates those exposed who may or may not go on to develop infection or become infectious.

Perhaps another similarly related topic necessarily relevant to the COVID-19 Pandemic is social distancing.

Quarantine or isolation of either exposed or infected persons can prevent further transmission. Quarantine or isolation alone do not help those that are already infected. Though if quarantine/isolation occurs in a medical setting, targeted help for the sick might reduce their morbidity and mortality.

A prominent recent example for the use of quarantine and isolation was during the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. No drugs or vaccines were available, and quarantine and isolation were the main control strategy. However, these public health actions considerably blundered without effective communication. The importance of isolation for Ebolavirus-infected persons was not adequately conveyed, and, consequently, public health efforts were met with considerable push back from local families who did not want their loved ones taken from them. Moreover, as Ebolavirus transmission can occur postmortem, the substantial mortality rate coupled with logistical issues for safe burials led to horrific scenes where bodies were left in the open waiting to be buried. In culmination, many ignored or blatantly disregarded the public health messages and concealed that loved ones were infected or that recent deaths were from Ebola.

These days, strict quarantine can be hard to enforce, especially for diseases that are not as severe as Ebola. A broader class of intervention strategies, of which quarantine is a strong form, often goes by the name of social distancing interventions. For example, closing a school to stop an ongoing flu or measles outbreak would usually not be labeled as quarantine, but would be considered social distancing. In general, social distancing interventions try to reduce mixing of infected and susceptible people, usually without going as far as fully isolating/quarantining individuals. In this way, social distancing could be thought of as an agnostic approach to quarantine/isolation where populations are separated without knowing exposure and/or infection status. This makes the intervention both less effective and less restrictive. Finding the right balance between restricting individual freedoms and protecting society can be difficult.

Another non-pharmaceutical intervention that has profound long-term effect is sanitation. By ensuring individuals have access to clean water, and waste is properly disposed of, the incidence of many ID dramatically drops. In fact, better living conditions resulted in reduced incidence for almost all IDs in Europe and North America even before the introduction of antibiotics. These are commonly called diseases of poverty. Closely related, hygienic behaviors (e.g., hand washing) can further inhibit the spread of IDs.

While usually not considered ID interventions, a general improvement in health (e.g., better nutrition), living conditions (e.g., better housing), and health literacy (better education) are known to be very effective at reducing the burden of any disease. Unfortunately, such systemic interventions are among the mostly costly and hardest to achieve.

11.4.4 Special Interventions for Non-human Hosts

If one of the hosts is not a human (e.g., a mosquito vector, or some other animal), it is possible to use interventions that are not feasible for humans. Widespread killing of mosquitoes is ethically acceptable (though often not too effective). The killing of mammals, e.g., culling of dogs in certain parts of the world to prevent the spread of rabies or other diseases, is more controversial. For some animals, ethical concerns are usually not too great (e.g., killing of poultry), but economic implications can be huge.

11.5 Characteristics of Interventions

In addition to grouping interventions into specific classes as done above, it is also useful to think about them in terms of their overall characteristics.

Temporal/timing characteristics: While some interventions are permanent or long-term, e.g., vaccines, sanitation, improved living standards, other interventions are short-term, such as drug treatment or quarantine. In general, those interventions with lasting effects are preferable. However, those are also often the most expensive and difficult to implement.

Target group characteristics: Another way to distinguish ID interventions is by the target group. Vaccines are ideally given before someone becomes infected with the ID (i.e., primary prevention). Drugs, on the other hand, are usually given to infected persons (i.e., tertiary prevention); though, pre-exposure prophylaxis is sometimes used, e.g., for HIV or flu during a pandemic. Quarantine can be applied to either susceptibles or infected. Measures such as sanitation improvement affect everyone.

Scale of impact characteristics: By that, I refer to the primary target being the individual or the population. The primary goal of drugs is to help the individual - population level effects as discussed earlier are secondary. In contrast, quarantine primarily targets population level impacts. It might not help an individual infected host if they are quarantined (though ethically, they should receive whatever support can be provided). Vaccines are also primarily meant to help protect the individual getting the vaccine. However, the effect of good vaccines is so powerful that in planning vaccination strategies, secondary population level effects due to herd immunity are nowadays taken into account. Interventions such as sanitation almost always target whole populations (e.g., a village/town/country).

Of course, for many interventions, these categories are not clear-cut and overlap. Still, it is conceptually useful to think about interventions in such broad categories. By looking at all the tools available and assessing their impact and feasibility, one can try to come up with the best strategy for a given ID and scenario. Such a best strategy will often involve using more than one method.

11.6 Impact of Interventions

We discussed previously that to eradicate a disease (or prevent local outbreaks) one has to get the effective reproductive number to just a bit below 1 (of course the lower and closer to 0, the better). The level of population protection at which R=1 is called critical herd/population immunity level. The relation between original/basic reproductive number, intervention coverage, and effective R is R= R0(1-p). That’s true if we assume that the intervention fully protects those to whom it is applied. If instead, the intervention is not perfect, we have R=R0(1-e*p), where e is the effectiveness of the intervention (e=1 is a perfectly effective intervention).

By discussing intervention coverage, we assumed that the intervention was applied to the susceptibles. However, the same idea also applies if the intervention is applied to infected. Recall that the reproductive number is given by \(R = D \beta S\). Reducing the fraction of susceptibles by some intervention reduces R. But we can also reduce R by reducing the duration of the infectious period, D, or the infectiousness/rate at which an infected transmits, \(\beta\). Quarantining infected is a strategy to reduce \(\beta\), drugs sometimes can reduce D and \(\beta\). For instance, if we can reduce the duration of the infectious period in the average infected person by p, we get a new effective reproductive number \(R_{e} = D(1-p) \beta S\). Obviously, the best strategy is one where we altogether reduce the duration of infection, transmissibility, and number of susceptibles by some fraction, thus leading to a potentially large reduction in R.

11.6.0.1 Efficacy vs Effectiveness

Both efficacy and effectiveness refer to the quality or effect size of an intervention, there is often a subtle distinction made between the two.

Efficacy generally refers to the effect size of an intervention in controlled, sometimes ideal, settings. For example, a randomized controlled trial reports a drug efficacy of 20%; the case fatality rate for those who received the drug during infection was 20% lower than for those who did not receive the drug during infection, i.e., \(Efficacy=\frac{CFR_{no~drug} - CFR_{drug}}{CRF_{no~drug}} = \frac{0.5-0.4}{0.5} = 0.2~or~20\%\) (a.k.a. an attributable proportion). Another way to think of efficacy to rearrange this equation to include relative risk. For example, \(RR=\frac{CFR_{drug}}{CFR_{no~drug}}=0.8\) and \(Efficacy=1-RR=0.2~or~20\%\).

Effectiveness, on the other hand, refers to the effect size of an intervention in the real-world settings. While efficacy studies may limit study participation to people with certain characteristics (e.g., healthy people aged 18-55 years), approach treatment or intervention with a strict protocol (e.g., initiate treatment immediately following positive diagnostic test), or even take measures to ensure compliance (e.g., taking drugs as prescribed), an effectiveness study would not have such involvement. As such, any differences during the practical implementation of the intervention could very well impact the measure of effect size. So, efficacy could be thought of as an upper bound for effectiveness.

To further complicate our understanding, vaccines offer an additional dimension to efficacy and effectiveness. Immunity is not simply a yes or no status and may exist along a continuum of strength and potentially act on infectious agents at different times during their life cycle. This allows interesting scenarios: a vaccine may induce immunity to an extent where a person is not able to be infected; the vaccine may only induce a partial immunity where a person is only protected from serious complications of infection (a.k.a disease-protective immunity/vaccine); or, a vaccine may induce immunity that neither protects against infection nor disease, but instead prevents transmission of the infectious agents. So, it is not only important to note the efficacy of a vaccine as number, but also to consider how it acts on the life history of the infection.

For an example, vaccine development against malaria (disease caused by parasitic infections of Plasmodium spp.) has been research on all these fronts as the parasite has antigenically-distinct life stages that contribute to the initial establishment of infection, the development of disease, and transmission. Although, no efficacious vaccine has been created yet.

11.7 Interventions and Models

Studying the potential impact of interventions is probably the single most important current use of ID models. It is often simply not possible to do field studies or experiments to test the impact of specific intervention strategies. Such field studies would take a long time, be very costly, be logistically hard to do, and often be simply unethical: We can’t introduce Ebola into a population, just to see how effective different intervention strategies might be! Thus, we rely on modeling to investigate hypothetical scenarios. Models are relatively easy and quick to build and analyze (at least compared to real field studies), there are no ethical problems, and we have ‘full control’ over the whole system and ‘know everything.’ The hope is that if our models are decent approximations of the real world, we can make informed decisions and prepare for future outbreaks.

11.8 Summary and Cartoon

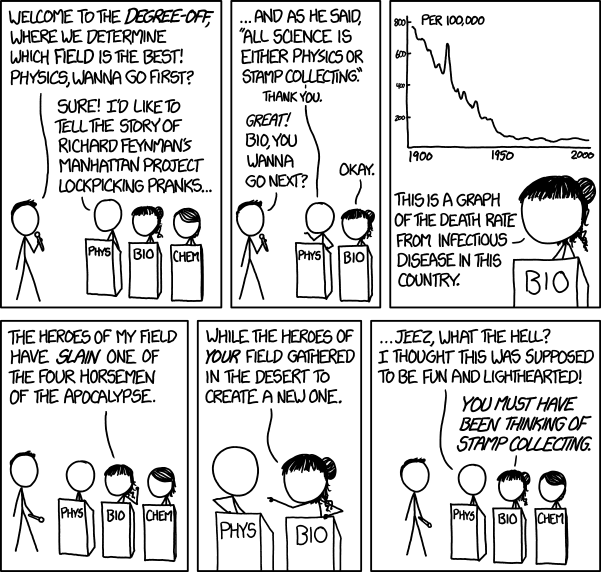

Infectious disease control is arguably one of the greatest successes of epidemiology and biology.

11.9 Exercises

- There are several ID Control apps in the DSAIDE package which provide hands-on computer exercises for this chapter.

- Read the article “Towards the endgame and beyond: complexities and challenges for the elimination of infectious diseases” by Klepac et al. (Klepac et al. 2013). Choose some ID - either one listed in box 1 of the paper or a different one - and discuss the current plans for elimination/eradication. What features of the ID will likely be helpful or unhelpful with regard to eradication/elimination? Reference the different areas the paper discusses? What is your overall assessment of feasibility?

11.10 Further Resources

- The relatively new Dengue vaccine raises interesting questions regarding the interplay of vaccination coverage and disease severity and is analyzed for instance in (Ferguson et al. 2016).

- A brief discussion of ID control is provided in (Halloran and Longini 2014).