Chapter 6 Types of Infectious Disease Transmission

6.1 Overview and Learning Objectives

In this chapter, we will introduce different types of ID transmission and how these different modes of transmission impact ID dynamics. Several of the following chapters will go into more detail on different modes of transmission.

The learning objectives for this chapter are:

- Know the different types of ID transmission

- Understand the implications different modes of transmission have for ID dynamics and control

6.2 Introduction

The way in which an infectious disease transmits is important to understand its transmission dynamics and for planning interventions. Classic infectious disease epidemiology approaches characterize transmission with the chain of infection: from an infectious agent leaving one place through some portal of exit to arrive via some mode of transmission at another portal of entry in a new place to grow. These generalizations are useful for understanding the basics of germ theory and align well with causation philosophies (e.g., Koch’s postulates), but to appropriately and effectively intervene, a deeper understanding is needed. Enter the plethora of classification systems found in modern epidemiology. It is now commonplace to hear infectious diseases referred to according to these broad categories (e.g., an acutely-infectious waterborne disease) and they are, at times, very useful in conveying not only accurate but also relevant information. Other times, combinations of non-mutually-exclusive categorizations and varying definitions in terminology lead to unnecessary confusion and, subjectively, ridiculous verbiage. However, it is important to be familiar with some of the terminology and classifications, but only with the understanding that dogma does not exist and standardization is not frequent nor, some would argue, possible.

6.2.1 Volatile Terminology

Using the chain of infection model, an infectious organism must come from one place, be transferred by some mechanism, and then arrive at some new place (typically, a susceptible host to infect).

Where the infectious organism comes from can loosely be referred to as a reservoir which includes both living and nonliving habitats Merrill (2013). To further break that apart, those living reservoirs may be referred to as carriers of an infectious disease Merrill (2013). Sometimes the word carrier is used to refer to other human hosts while other times it could refer to another animal; the meaning lying with the author’s discretion. Furthermore, there are several more sub-categorizations of carriers which can relate to their disease status/natural history of infection (e.g., asymptomatic, healthy, convalescent). Sometimes, a line is drawn between vertebrates and invertebrates with the former being referred to as carriers causing zoonotic diseases while the latter are called vectors causing vector-borne diseases Merrill (2013). However, what constitutes a vector is extremely variable and sometimes doesn’t refer to a living organism at all (e.g., HIV transmitted via infected needles) (Wilson et al. 2017). Other examples of nonliving reservoirs might include water, soil, or fomites (i.e., surfaces; e.g., doorknobs).

To simplify a bit, an infectious disease can be transmitted directly or indirectly. Although, among indirect ways of transmission, there are again different important categories, such as environmental or vector-borne transmission. Again, it is often things are not that clear-cut: some diseases might transmit by more than one route, and the definition of direct and indirect is not as straightforward as it might sound. The following paragraphs briefly discuss these main different transmission modes, which will then be discussed in more detail in the following chapters.

6.3 Direct Transmission

The most straightforward way of transmission is direct transmission from infected to uninfected host. The clearest examples of direct transmission are sexually transmitted diseases. It is generally the case that direct physical contact between infected and uninfected host is required for transmission. Exceptions exist, such as transmission of HIV through infected needle sharing, which could even be considered a type of vehicle-borne or, sometimes, vector-borne transmission, but non-direct modes of transmission are not common.

Respiratory diseases are often also considered to transmit directly if close proximity between infected and uninfected host is needed for successful transmission. Examples are measles and influenza. It gets a bit tricky though since many respiratory pathogens can also transmit by first being deposited in the environment (e.g., inside tiny water particles floating in the air a.k.a. aerosols, or on a bathroom faucet). Then if an uninfected person comes into contact with the contaminated environment (i.e., breathes in contaminated tiny water particles), they can get infected. It is common to see the transmission of these respiratory diseases further subdivided into droplet or airborne transmission. The distinction lies with the size of the aerosols produced and, consequently, how long the aersols/pathogens are able to linger in the air. Droplet transmission refers to “larger” water particles which fall to the ground relatively quickly and at shorter distances and is sometimes considered direct transmission; while, airborne transmission refers to “smaller” water particles which can linger in the air for a significant amount of time and could potentially travel larger distances and is sometimes considered indirect transmission. These distinctions are often made in hospitals with isolation precautions: isolation precautions for droplet transmission (e.g., for diseases such as the flu or whooping cough) indicate the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) including a surgical mask (often with a face shield); isolation precautions for airborne transmission (e.g., for diseases such as measles or tuberculosis) are much more intensive and indicate the use of PPE including N-95 masks (a much more intensive mask) and also that patients be placed in negative-pressure rooms (i.e., rooms where air is continually sucked out). Moreover, you might hear of a safe-distance (e.g., 3-6 feet or 1-2 meters) as a guideline for droplet transmission, but these distances would not be considered safe for airborne transmission. The importance of direct versus indirect/environmental transmission for many respiratory pathogens is still not fully understood, and can likely differ between different settings.

Another path of direct transmission is from mother to baby before or during birth. This is often called vertical transmission, while all other forms discussed above and below are called horizontal transmission. HIV is an example of a pathogen that can transmit via both routes.

6.4 Environmental Transmission

As just mentioned, respiratory infections might spread through an environmental stage, where the environment is small water particles in the air or on solid surfaces. Environmental transmission is sometimes referred to as vehicle-borne transmission where a vehicle refers to the nonliving reservoir through which the pathogens are transmitted (e.g., an infected needle, food, clothes) Merrill (2013). Infected surfaces (in the context of ID transmission often called fomites) are major routes of transmission for several important pathogens, for instance, Staph or pathogens that transmit through the fecal-oral route, e.g., norovirus. Water is the main transmission environment for another important fecal-orally transmitted disease, Cholera. The chapter on environmental transmission will discuss this route in more detail.

6.5 Vector-borne Transmission

Diseases that transmit through a vector stage, such as Malaria, Dengue, Zika, and others, are an important category. As previously mentioned, vectors are sometimes considered any invertebrate which can transmit a disease. The transmission could be mechanical (e.g., flies transmitting Vibrio cholera) or biological (e.g., mosquitoes transmitting Plasmodium falciparum) with the distinction made in whether the infectious agent infects or reproduces within the vector.

One of the more common definitions of vectors limits it to hematophagous arthropods (i.e., arthropods that feed on blood, e.g., mosquitoes, ticks, some flies). Mosquitoes are the most common and most important vectors, but other vectors are also important (e.g., kissing bugs for Trypanosoma, which causes Chagas disease).

The definition of what makes an ID a vector-borne ID is tricky. See the HIV-needle example above, or consider Zika, which can transmit by multiple routes. For some diseases, it is not clear if one should consider them vector-borne or not. This obscuration extends for infectious diseases with complex, or multi-host, transmission. For instance, Toxoplasma gondii spends part of its life-cycle in cats, and the other part can be in another host, most commonly mice or birds. If the latter type of host should be considered a vector or not is largely a matter of definition. Often, it is called an intermediate host, and T gondii and diseases with similar life-cycles (e.g., Schistosomiasis) are considered multi-host diseases, with the term vector-borne mainly used when the intermediate (non-human) host is an insect.

6.5.0.1 Complex Transmission Hosts

Often in complex, multi-host transmission, there are distinctions made among hosts. Definitive hosts (a.k.a. primary hosts) are those in which the parasite completes sexual life stages or reaches an adult stage (e.g., mosquitoes for malaria-causing Plasmodia). Intermediate hosts (a.k.a. secondary hosts) are those in which parasites develop (sometimes as sexually immature life stages) or replicate asexually (e.g., humans for malaria-causing Plasmodia). Additionally, if a parasite infects a host which can not further its transmission, this host is called a accidental or dead-end host (e.g., humans and horses for West Nile Virus).

6.6 Hope on the Horizon

Despite all these exhausting classifications and inconsistent definitions, the practical approaches to modeling split fewer hairs. That is, much of the subtlety in the infectious disease biology is not needed for representation in an infectious disease model. As we will see, from the perspective of describing such diseases with models, the labeling does not make much of a difference. It is more important that the models capture key mechanistic differences which may impact the transmission dynamics. However, it is still important to understand the terminology and essential to understand the inconsistency. Always ensure you understand the author’s definition before attempting to digest their work. For this book, the more general definitions of the discussed terminology will be used and it should be clear which definition is being used.

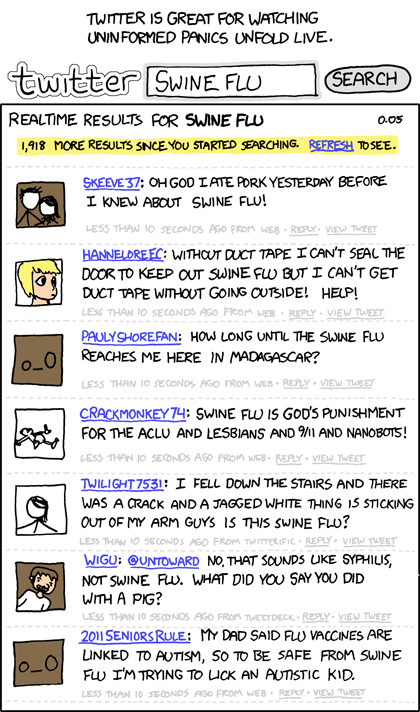

6.7 Summary and Cartoon

This chapter briefly introduced different modes of ID transmission.

Knowing transmission routes is important to understand how one can and cannot contract a specific disease. Source: xkcd

6.8 Exercises

- Several apps in the DSAIDE package address specific types of transmission, those are discussed in the following chapters.

6.9 Further Resources

- A detailed discussion linking transmission types to model alternatives is provided in (Hamish McCallum et al. 2017).