Basic Statistical Models

Overview

In this unit, we will discuss a few basic, common models.

Learning Objectives

- Learn about several types of basic models.

- Understand the relation between basic models and statistical tests.

Introduction

There are lots of models out there. It is fair to say that nobody is familiar with all of them. There are however several often-used types of models that everyone doing data analysis should be familiar with. These models are easy to implement and often surprisingly useful and powerful.

You are likely already familiar with these models. In fact, at some point you probably have taken - or should if haven’t - a course just on those models.

Simple models for continuous outcomes (regression)

The most common model type applied to continuous outcomes is a linear regression model. This model is covered in many of the course materials we have been using (and of course other places).

Advanced Data Science – which used to be part of the old IDS – has a chapter on it. ISLR also has a chapter on the topic. So does HMLR.

This is such a fundamental type of model and is thus covered in a lot of resources. There are plenty more available, including the good old Wikipedia. Find some you like and read/learn enough about these models that you feel comfortable understanding conceptually what they are used for and how they work.

Simple models for categorical outcomes (classification)

For categorical outcomes with 2 categories (also called binary or dichotomous outcomes), logistic regression is the most common approach. You might be wondering why this method is called logistic regression even though it is used for classification. This is because logistic regression predicts the probability – a numeric value between 0 and 1 – of having the outcome. These predicted probabilities are then turned into yes/no predictions (i.e., classifications) using a cut-off, usually (but not always) a probability of 0.5. Probabilities below that cut-off are classified as 0/not present/no and above that as 1/present/yes.

To learn about logistic regression, or refresh your knowledge if you have previously been exposed to those models, read through the Logistic Regression chapter in HMLR. This reading goes into maybe more detail than you want or need at this point. So just make sure you go through it to get the main points of what logistic models are all about. We’ll come back to some of the other topics discussed there later.

Logistic models are also covered in the Classification chapter in ISLR. Read through the first part of this chapter in enough detail to get the overall concepts. You can also go through the sections following the logistic regression section to learn about some additional methods for classification. We’ll revisit some of those types of models later.

Of course, you can also find lots of additional resources online describing logistic regression models. If you find a good one, let me know.

Generalized linear models

Both linear and logistic models belong to a class of models called generalized linear models (GLM). Those types of models allow you to fit outcomes of specific types, for instance, if you have outcomes that are counts (integers), you can use Poisson regression, or if you have continuous outcomes that are all positive, you could use a Gamma regression.

GLMs all have the same structure: namely there is a linear combination of predictor variables (e.g., \(b_1*age + b_2*height\)) and those are connected to the outcome through what is called a link function.

GLM are very commonly used. Among GLM, linear and logistic regression models are by far the most commonly used ones. Other models that assume specific distributions of the outcome, e.g. a Poisson distribution, can be accommodated by choosing the appropriate link function, which connects a linear combination of predictor variables with the outcome. GLM models are fast and easy to fit (using e.g. the glm function in R), fairly easy to interpret, and often provide performance that is hard to improve upon with more complicated models, especially if the data is on the small side. To prevent overfitting, variable/feature selection or regularization approaches are often used. GLM assume a specific relation between predictors and outcome (e.g. linear, logistic) and as such might not perform well on data that does not show the assumed pattern.

At the end of the Classification chapter in ISLR, there is a nice brief discussion of GLMs, I suggest you read through that in enough depth to get the overall ideas, but there is no need to go through all the math.

KNN - another simple model worth mentioning

Another model that you might have already encountered (e.g., in the ISLR reading) is one called k-nearest neighbors (KNN). The idea is very simple: For any new observation, you compare the values of the predictor variables with those in your data. You then predict the outcome of the new observation to be the average of the outcomes of the K observations whose predictors most closely resemble the predictors of the new observation.

As an example for a continuous outcome (regression), if you want to predict height as the outcome and you have age and weight as the predictors, you would take an observation, look at the age and weight values for that observation/individual and compare to the K individuals in your dataset with the closest values (we won’t go into detail how “close” is defined). Then you take the average height of those K closest individuals and that’s your prediction for the new observation.

The same idea can be applied to categorical outcomes (classification). Say you wanted to predict sex instead of height. You again looked at the K individuals whose predictor values (here age and weight) are closest, and use the majority to predict the outcome for the new observation. (Say K=5, and 3 of the 5 closest individuals are male. Then you would predict the new observation to be male.)

KNN often perform well, but they are not very “portable”. For other models, once you trained/fit a model, you can “take it with you” and apply the model to new data, leaving the old data you used for model building behind. KNN are a somewhat strange since the data is the model. All the data is used to predict new observations by comparing them to existing ones and predicting outcomes based on closeness of predictor variables. Which means you always need to have the data to predict new outcomes, often making it not too useful in practice. You also don’t learn too much in terms of inferential insight. Still, it is a useful model to know about, and it works for both continuous and categorical outcomes. It is also commonly used for imputation of missing values. In that situation, you treat the predictor you want to impute as the outcome and use the remaining predictors as the data. KNN are described in the K-Nearest Neighbors chapter in HMLR and also show up in chapters 2 and 3 of ISLR and the Cross-validation and Examples of Algorithms chapters of IDS. Take a look at any of those resources if you want to learn a bit more about KNN.

Simple models for no outcomes

As we discussed previously, if you have an outcome variable, your data is called labeled data and the methods you use are called supervised methods/models. Such data with one (or several) outcome variable(s) are most common. But as previously discussed, sometimes you might have data without clear outcomes (unlabeled data) and you still want to determine if there is some pattern in your data. This calls for unsupervised methods.

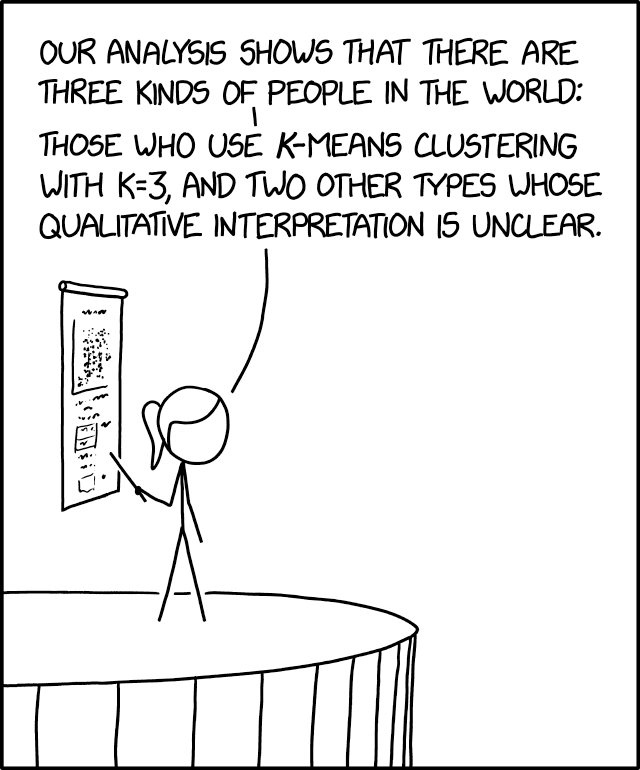

There isn’t really one single, standard go-to method for unsupervised learning – in contrast to the very common linear and logistic models for supervised learning. There are often used methods, such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) (which falls into a larger group of methods called dimensionality reduction methods) and a group of methods called clustering methods (the most common among these are probably k-means clustering and hierarchical clustering). Since most of you will work on labeled data using supervised methods most of the time, we won’t go much into unsupervised methods. If you want to learn a bit more, check out for instance the Unsupervised Learning chapter of ISLR. There are also chapters on PCA and different types of clustering in HMLR.

The zoo of statistical tests

In some of your (bio)statistics classes, you likely came across a variety of statistical tests, e.g., t-test, Wilcoxon, Kruskal-Wallis, and others from the huge collection of tests. Each test makes certain assumptions and is most adequate for certain types of data. For instance you might remember hearing about parametric tests (which are most applicable if the underlying data has a certain distribution, usually a normal distribution) and non-parametric tests, which make fewer assumptions about the distribution of the data, but don’t have quite the same statistical power. Those more traditional statistical tests certainly have their uses (though are quite often overused and misused). We just don’t have time to cover them.

Pretty much all of those tests have equivalent formulations as multivariable models (either a GLM type as described here, or others that we’ll cover later). The advantage of more general models, such as GLM, is that they easily allow for as many predictor variables as you want to add. Also, once you understand the general setup of GLM (and other models), this understanding transfers to other methods. For statistical tests, they are often taught as “if the data look like this, then test like that” without any underlying fundamental and transferable understanding. Overall, I am not a big fan of the way many intro (bio)stats courses are still taught these days.

Because of that, and since this course is about modern data analysis, we will not cover any classical statistical tests and instead start with multivariable, GLM-type models and then move on to more complex/modern machine learning models.

If you never thought about the relation between classical statistical tests and GLM-type models, you might want to check out Common statistical tests are linear models by Jonas Kristoffer Lindeløv which explains the relation between the two in a good bit of detail. Statistical tests as linear models by Steve Doogue is also good, it is based on the original text by Lindeløv and covers some topics in more detail. Both resources show examples in R, and have links to further materials. At some point in your career as a data analyst, you might need to use or interpret classical statistical tests, and having a general idea that they can map to GLM-type and other models might be helpful.

Further reading

Chapters 3 and 4 of ISL discuss linear and logistic models. So do chapters 4 and 5 of HMLR.

For another source that discusses almost all the models just mentioned, each one very briefly, see the Examples of Algorithms chapter in IDS.