Model performance metrics

Overview

This unit discusses the idea of assessing a model based on its performance through some metric.

I use the term model performance here in a narrow sense, quantified through some metric.

Learning Objectives

- Understand the concept of model performance.

- Be aware of different common metrics to assess model performance.

This unit contains some equations showing explicit definitions for a few common performance measures. They are fairly simple and I’m sure you’ll be able to follow once you spend a few minutes to think through them. If you don’t like reading equations, you should be able to just jump over them and still understand what is going on. Most often, your software will do all computations for you. But sometimes it doesn’t. It is therefore good to know a bit how common performance measures are defined. Once you do, you realize that you can simply compute them yourself with just a few lines of R code.

Introduction

When you fit a model (e.g., a linear model or logistic model) to data, what exactly happens? What does it mean when we ask the computer to fit a model? Think about what’s going on for a minute.

Model performance

What your fit a model to data, your computer varies the parameters of your model to improve model performance, until there is no more performance improvement possible.

We generally want a well-performing model to be one that captures the main patterns in the data as closely as possible.

To provide a specific example, let’s say you want to fit a multivariable linear model to some outcome \(Y\) given some predictor variables \(X_i\) (e.g. fitting/predicting weight of a person, given their height and age). The model equation will look like this:

\[Y_m=b_0 + b_1X_1 + b_2X_2 + \ldots + b_n X_n.\]

When you ask the computer to fit this model, it will guess some values of the coefficients bi and then vary them (in a smart way)1 until the predicted Ym (often also called \(\hat{y}\) or \(\hat{Y}\)) from the model are as close as possible to the actual data values Yd (often also just called \(y\) or \(Y\)).

The overall procedure of adjusting model details until you get a model that capture the patterns in the data as best as it can, and has the highest possible performance, is very general and applies to any kind of model, as well as both continuous and categorical outcomes.

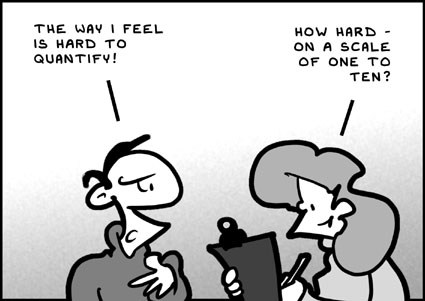

What is important that for each scenario, model performance is clearly defined. What you mean by model being close to data or model capturing the pattern in the data needs to be to specified such that your algorithm can compute a number that it can try to optimize - the performance metric.

It is important to be aware that the choice of the performance metric is a scientific choice. You need to specify it based on your knowledge of the system and the question you want to answer. While there are very common performance measures, which we will discuss next, it is important that you do think about what it is you are actually asking your model to do and what you optimize when you fit data.

The cost/loss/objective function

To specify a performance metric/measure we want to optimize, we need to define some function of both model predictions (Ym) and measured data (Yd) outcomes. This function goes by different names, but the terms most commonly used are cost function or loss function. In more general math or stats context, this is also called an objective function. Other names are common in different areas of science, see e.g., those listed in the linked Wikipedia article.

Another term is simply metric. I’m also calling it generically performance measure here. I often interchangeably use these terms, so just be aware that they mean the same thing: a function that is used to measure how close the model predictions are to the data.

The convention is to set up the problem such that larger discrepancies between model and data lead to a larger numerical value of this function. Then our goal is to minimize the objective function, which means minimizing the difference between the data and the model predictions. (Occasionally, problems are set up to maximize this function. You can always change it into a minimization problem by e.g., taking the inverse or adding a minus sign.)

In equation form, we have in the general case: \[C = f(Y_m,Y_d).\]

The \(Y_m\) are all the predictions made by the model for the outcome, and the \(Y_d\) are the actual outcomes from the data. You need to specify some function, f, that uses all those values to compute a single value to measure your performance. The different types of functions, f, depend on the type of data and other considerations. Once you define f, this is the performance metric which quantifies how well a given model fits the data.

When you do a single model fitting step, the computer calculates f for different values of the parameters, bi. In general, it repeats this for different values of the model parameters until it finds the ones that produce the best (i.e., minimum) value of C.2

Similarly, if you fit two different models (e.g., a linear model with 3 predictor variables, and another one with 5), you can use the value of C to compare model performance. We’ll get into that in more detail in further units.

Cost/loss/objective functions for continuous outcomes

Least squares

You are likely familiar with one of the most widely used functions for f, the least-squares method. If you have ever fit a linear model (e.g. using lm() in R or an equivalent function in a different statistical software), chances are you used least squares as your objective function (maybe without knowing that you did). For least squares, we compute the squared difference between model prediction and data for each observation and sum it all up. In equation form:

\[C = f(Y_m,Y_d) = \sum_i (Y_m^i - Y_d^i)^2\] Again, \(Y^i_m\) are all the predictions made by the model for the outcome, and the \(Y^i_d\) are the actual outcomes from the data. The quantity \(C\) for this equation has many names. A common one is least squares error, or sum of square residuals (SSR), or residual sum of squares (RSS), or sum of squares (SS), or residual square error (RSE), and a bunch of similar names. You will usually be able to tell from the context what is being used as the performance metric.

You will often see a variation where one divides by the sample size, i.e. \(C\) will look like

\[C = \frac{1}{N} \sum_i (Y_m^i - Y_d^i)^2\]

This is called mean squared error (MSE). Of course, other names exist.

Dividing by the sample size has the advantage of allowing you to compare values across samples of different size from the same dataset (but it doesn’t really work for comparing across different datasets). For instance if you compare model performance on training and test data (to be discussed shortly), and each has different sample size, you need to make sure you standardize by it.

If you want to compare different models on the same dataset which might include some missing values, and one of your models can deal with missing data while the other cannot, you need to be careful. One option is to fit both models only to the data without missing values. If you decide to allow one model to use the observations that have some missing values, while the other model does not, you definitely need to standardize by the sample size. Even then, care is needed, since the samples with some missing data might be systematically different from those without and thus the datasets might not be equivalent anymore.

Another variant is a version where at the end you take the square-root, i.e.

\[C = \sqrt{\frac{1}{N} \sum_i (Y_m^i - Y_d^i)^2}\]

which is called the root mean squared error (RMSE). The advantage of taking the square-root at the end is that now the units of \(C\) are the same as those of your outcomes. THis often makes interpretation of the results easier. In general, it is best to use MSE or RMSE. In tidymodels, the yardstick package has the rmse() metric built-in.

Coefficient of determination

An equivalent alternative to SSR is to use a quantity called Coefficient of determination, or more commonly \(R^2\) (R-squared). This quantity is defined as \[R^2 = 1-RSS/TSS\] where RSS is the residual sum of square introduced above and TSS is the total sum of squares.3

The latter is defined as

\[TSS = \sum_i (Y_{av} - Y_d^i)^2\]

where \(Y_{av}\) is the mean of the data. Therefore, the equation for \(R^2\) is

\[R^2 = 1- \frac{\sum_i (Y_m^i - Y_d^i)^2}{\sum_i (Y_{av} - Y_d^i)^2}\]

Since TSS is fixed for a given dataset, minimizing SSR is equivalent to maximizing \(R^2\). You might see \(R^2\) reported in papers, and it is highly likely that the fitting was performed by minimizing SSR (or MSE or RMSE). The SST is a useful quantity since it tells us the performance of a dumb/null model which uses no information from any predictor variables, but instead just predicts the mean of the outcomes. Any model you build that includes predictors needs to do better than this dumb null model.

Least squares fitting is simple and frequently used. A lot of standard routines in major statistical packages use least squares. It often makes good sense to penalize predictions that deviate from the actual value with the squared distance (and under certain conditions, this is equivalent to maximizing the likelihood). However, sometimes a different way to define the function f might be useful. We’ll discuss a few of them briefly.

Beyond least squares

An alternative to least squares is to penalize not with the distance squared, but linearly with the (absolute) distance. This metric is called (mean) absolute error (MAE) or (least) absolute deviation, and the model is

\[C = f(Y_m,Y_d) = \sum_i |Y_m^i - Y_d^i|\]

This approach can be useful if the data contains outliers (that are real, and one can’t justify removing them during cleaning). With a squared distance penalty, outliers have a strong impact on the model fit. With a linear penalty, such outliers carry less weight. Because of this, the linear difference approach is sometimes called a robust estimation.

Robust estimation methods such as MAE are not as common as least squares, but most software has support for it. For instance, there are multiple packages in R that support MAE and other robust fitting methods.

You might wonder why we don’t just use those robust methods all the time, just to be safe. There are fundamental statistical reasons why optimizing the MSE is often more aligned with the question we want to address, so you should switch to a robust method only after you thought about it and decided it’s the right approach for your specific scenario. You can also always do it both ways and compare results to get an idea of the potential influence on your results from the outliers. Doing things more than one way – and of course reporting each approach you tried – is generally a great idea. This is often called performing a sensitivity analysis.

Another way to define f is with step functions. The idea is that as long as model and data are within some distance, the penalty is zero. Once model and data differ by some threshold, a penalty is given, e.g., a fixed value or a linear or quadratic penalty. Such types of schemes to define f are common in the class of models called Support Vector Machines, which we will look at later in the course.

No matter what scheme you choose, it might at times be useful to weigh data points. In the examples given above, each model-data pair was given the same importance. Sometimes it might be that you have some data points that should carry more weight. A common case is if you have measurements not on the individual level but some aggregate level. As an example, assume you have a fraction of heart attacks among all patients for some time period in different hospitals, and you want to fit that fraction. You don’t know the number of people who had heart attacks, only the fraction. But you do know something about the total number of beds each hospital has. You could then argue that hospitals with more beds have more patients and thus likely more heart attacks, and therefore the data from larger hospitals should get more weight, and you could e.g., multiply each term in the sum by bed size. Note that this is a scientific decision based on your expert knowledge of the data. Almost all fitting routines allow you to provide weights for your data and you can then perform weighted least squares (or a weighted version of whatever other approaches you choose).

Performance measures for categorical outcomes

For categorical outcomes, one needs different ways to specify the loss function/metric. Again, a lot of different options exist. Here, we’ll just discuss a few common ones.

Accuracy

The simplest way to determine performance of a model for categorical data is to count the fraction of times the model did (not) correctly predict the outcome. If we instead count the fraction of correct predictions made by the model, it is called accuracy. If we focus on the number of times the model got it wrong, it is called the (mis)classification error. The yardstick package has it as metric accuracy().

While accuracy is often not a bad choice of metric, sometimes just counting the number of times a model didn’t get it right might not be the best idea. A common situation where accuracy (just counting how often the model prediction is right/wrong) is not very useful is for rare (but important) outcomes. Data of this type is often called unbalanced data. As an example, say we had some algorithm that tried to use brain images to predict if people have brain cancer. Fortunately, brain cancer is rare. Let’s say (I’m making this number up) that 1 in a million people who undergo this screening procedure actually have this cancer. Therefore, a model that predicts that nobody has cancer would be a very accurate model, it would only make one mistake in a million. However, missing that one person would be a very important mistake. We likely would prefer a model that flags 10 people as (potentially) having a cancer, including the person who really does and 9 false positives. This model has worse accuracy since it gets 9 out of 1 million wrong. But it’s likely more important to catch the one true case, even if it means temporarily scaring several other individuals, until further checks show that they are healthy. Of course this trade-off is very common. You likely know it in the context of balancing sensitivity and specificity of say a clinical test. Other areas where this happens is, e.g., predicting the (hopefully rare) errors when building a plane engine, flagging the (rare) credit card fraud, and many others of that type.

Beyond accuracy

In instances where accuracy/misclassification is not a good performance metric, other metrics are more helpful. A large variety of such metrics exist. Some only apply to the special (but very common) case of a binary outcome, and others apply more generally. Fairly common ones are: (Cohen’s) Kappa, Area under a Receiver operating curve (AUC ROC), Matthews correlation coefficient and F-score.

The confusion matrix

For the common case of a binary outcome, one can construct what is called the confusion matrix (also known as 2x2 table in epidemiology). The confusion matrix tracks 4 quantities: true positives (TP, model predicts positive, and data is positive), true negative (TN, both model and data are negative), false positive (FP, model wrongly predicts positive) and false negative (FN, model wrongly predicts negative).

The confusion matrix comes with very confusing terminology since many of the quantities are labeled differently in different fields. For instance, epidemiologists tend to call the quantity TP/(TP+FN) sensitivity, while in other areas, such as machine learning, it is called recall. For a good overview of those different quantities and terminology, see this Wikipedia article.

One can of course also make a table for a case with more than 2 outcomes and track the true values versus the predictions. Some of the metrics generalize to such a scenario of more than 2 outcomes, but not all do.

Custom cost functions/metrics

There are many different performance measures that have already been “invented”. While one of the existing loss functions/metrics (e.g., those just discussed or other common ones) might work for your data and question, it is worth thinking carefully about what it is you want to optimize, i.e., how exactly the function f should work.

If no existing measure is suitable for your problem, you can and should define your own. Based on scientific/expert knowledge, you should define the most appropriate cost function and then measure your models based on that. Getting the cost function right is an important, and often overlooked part of the modeling process. For instance, revisiting the example I gave above, if we think that falsely accusing a person of being a criminal has cost (in some units, that could be monetary or otherwise) of 1, but missing to identify a person who is a threat has cost of 1000, then we should weigh false positives and false negatives accordingly when computing our cost function and designing our model. This is similar to applying weights in the continuous case.

Likelihood approach

The most general approach to defining the cost/loss function, f, is the likelihood approach. Using this approach, which underlies a lot of modern statistics, both frequentist and Bayesian approaches, you start by explicitly specifying a model/distribution for the data (both deterministic and probability parts). As an example, you might postulate that expected number of cases of Cholera in a given month depends linearly on the monthly amount of rainfall (deterministic component) and that the actual/measured number of cases are Poisson distributed (probability component). Both the deterministic and probabilistic components of your model have parameters. You write down (or simulate) the likelihood and then run some optimization routine which varies parameters until it found the optimal result (maximum of the likelihood, or more commonly the minimum of the log-likelihood).

Using the Likelihood is the most general and flexible approach to model fitting and for more complex problems, often the only feasible approach. It applies to any kind of outcome, and you can specify any model you want. Unfortunately, it is generally more complicated and often requires more custom-written code (though a lot more user-friendly R packages have become available in recent times). We can’t get much into likelihood-based fitting in this course. For more information, I recommend Ben Bolker’s book Ecological Models and Data in R as a good starting point for (mostly frequentists) Likelihood fitting approaches. Another book that introduces the ideas from a Bayesian perspective is Statistical Rethinking. Unfortunately, neither book is freely available online (as far as I’m aware). If you know of any good introductory books that teach model fitting using likelihood approaches with R, please let me know.

Summary

Without a full specification of your model performance criterion (objective function), you can’t fit a model to data. While there are common standards that people use without much thinking (e.g., least squares optimization), it is generally important to ensure that what you optimize is what you actually care about.

Further Resources

If you want to get some more intuition with fitting a continuous outcome, go through this interactive tutorial.

The Model Evaluation section of HMLR lists and describes various performance metrics. The Performance chapter of Tidy Modeling with R also discusses different performance metrics.

Chapter 2 of ISLR, which you already looked at previously, also discusses the topic of performance, and several other issues we are discussing in this module. Now, or once you are finished with the other readings of this module, might be good time to revisit that chapter.

The yardstick package from the tidymodels framework is all about metrics and has support for a large number of them. You can check out other metric types in this yardstick article.

Footnotes

This business of varying the model in a smart way until you find the best one is an example of what’s called optimization. Developing routines that can quickly, efficiently, and reliably find the optimum is a huge area, and depending on the model and data you are trying to fit, having smart algorithms to do the optimization can be very challenging. You can make a whole career just working on optimization topics. Fortunately, for most purposes, we can generally use existing software and rely on their built-in optimizers.↩︎

Technically, for some simple models, it is possible to find the best parameter values other than by ‘trial and error’, but for many other models, this is more or less what is happening.↩︎

Also called SST, sum of squares total.↩︎